Tremper Mound’s

Indigenous Legacies

Address: 20580 SR-73 McDermott, OH 45663

The Great Scioto River winding through the floodplain of Tremper Mound Preserve, Photo by Brian Prose

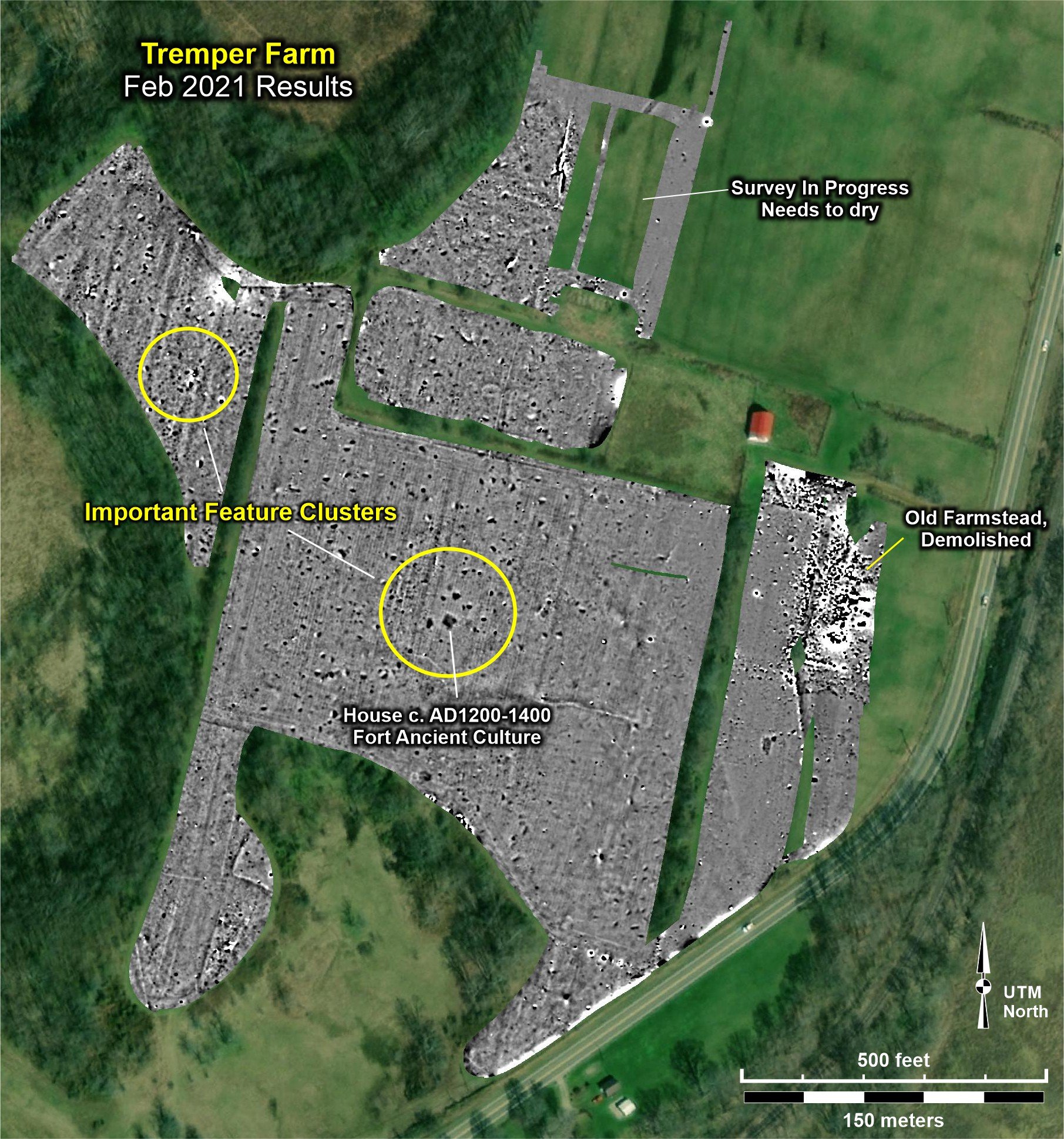

Magnetometry discoveries in the region south of Tremper Mound - part of the larger study area that was investigated for activities of earlier peoples. By Jarrod Burks

The Great Portsmouth Works and the features we know were part of this ancient 25-square-mile ceremonial landscape. Map by Emily Uldrich

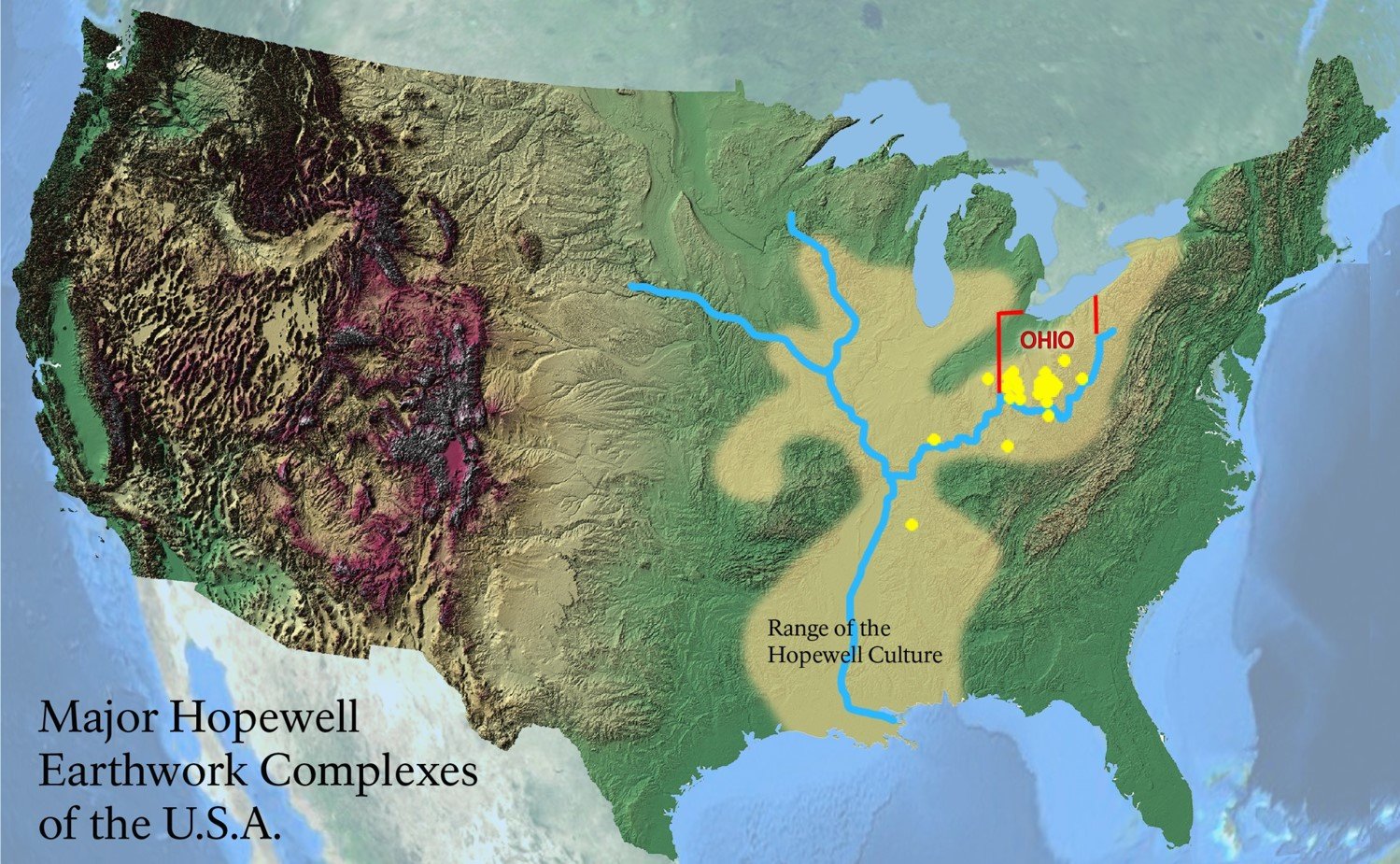

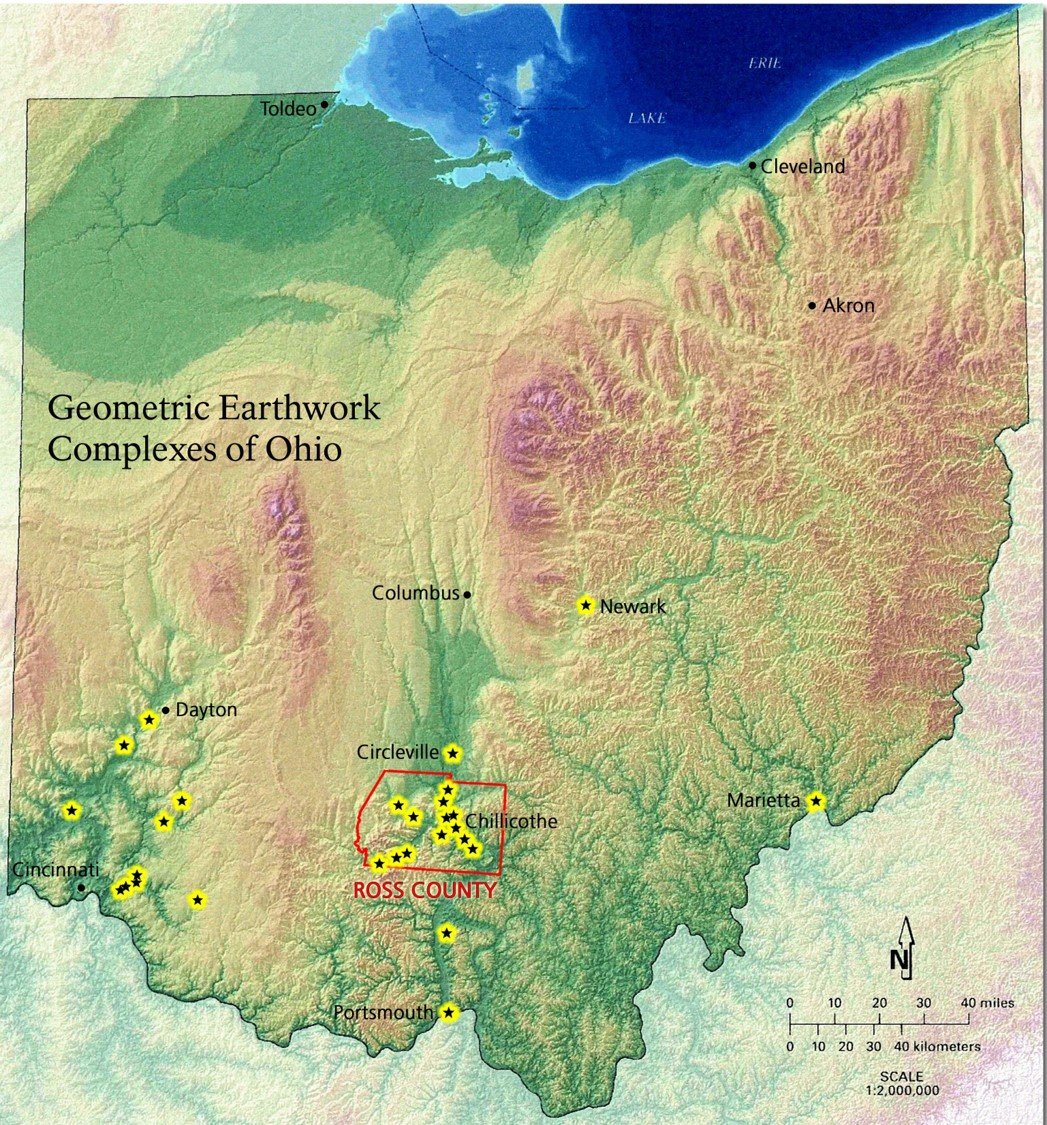

Ohio was the center of the Hopewell Culture activity and nearly all its great earthwork complexes are located along the great waterways of southern Ohio. Map courtesy of Hopewell Cultural National Historical Park.

Mica Bear that was found in Tremper Mound

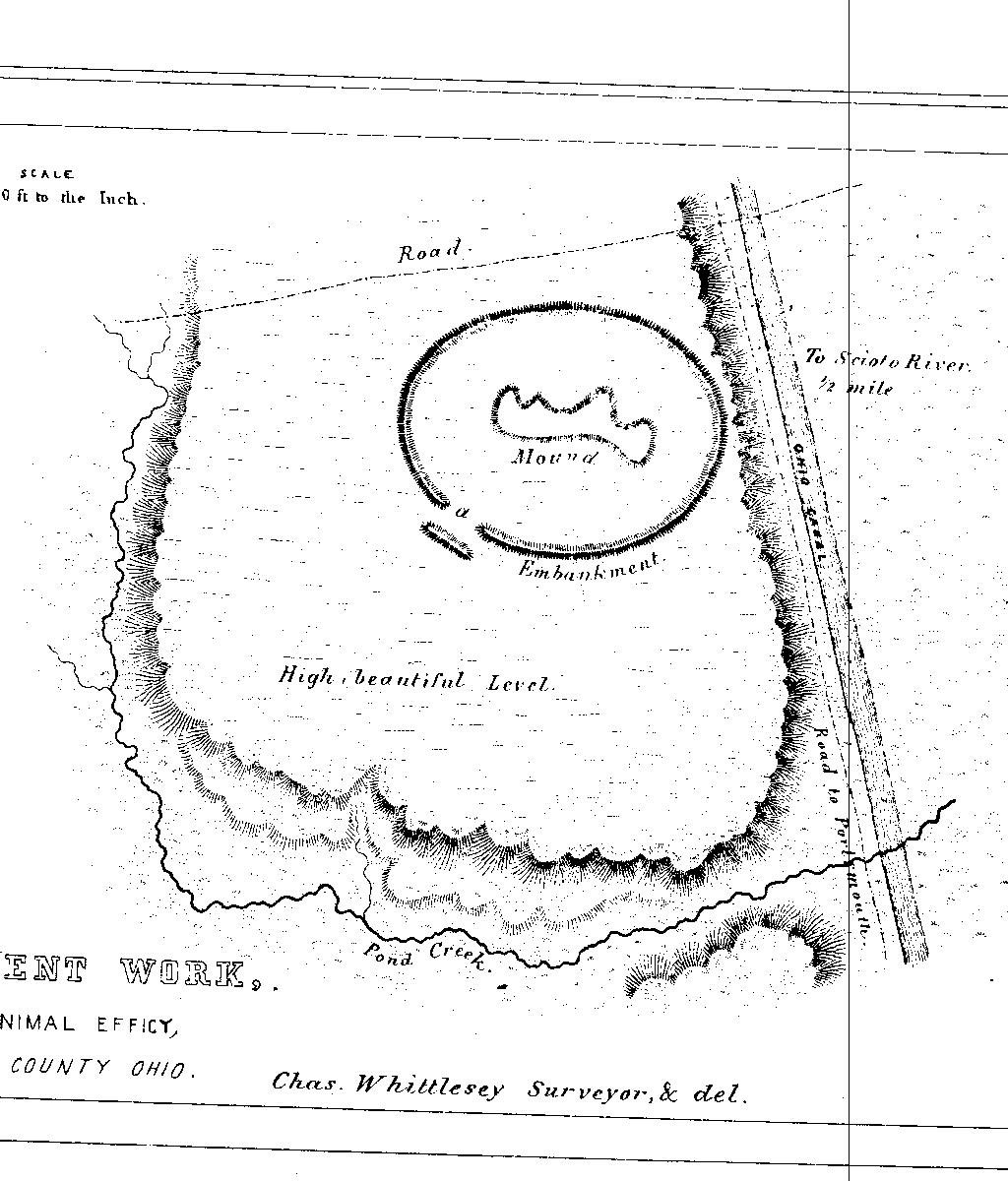

A beautiful pre-excavation survey of Tremper Mound by Charles Whittlesey, prepared for the Smithsonian Publication: Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley

“Tremper Mound and Enclosure” (2022) artwork designed by Herb Roe for the Scioto Historical Project of the Center for Public History at Shawnee State University.

Drawing from the 1915 excavation of Tremper Mound, showing the location of the wooden poles that once supported the Greathouse and defined its many partitions and chambers.

Aerial Photo of Tremper Mound Today by Steve Plattner. The mound is now selectively mowed to help distinguish it from the surrounding landscape.

Many Hopewell earthworks show remarkable astronomical alignments, marking such celestial events as solstice and lunar standstill points on the horizon. Photo Courtesy of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park

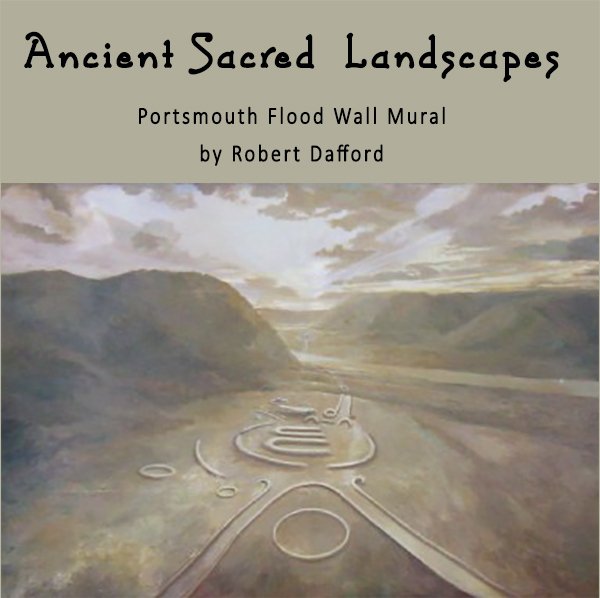

A Portsmouth river wall mural showing the Great Portsmouth Works and the Hopewell Culture's remarkable engineering feats near the Ohio River

A Beaver Pipe - The animals selected by the carvers of the Hopewell Culture for their platform pipes included animals both great and small.

The Hopewell Culture crafted roughly 36 large and complex ceremonial centers. All of them incorporated earthworks that were constructed with geometric symmetry and precision. Map by the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park.

This mural, painted by Robert Dafford and showcased in the Appalachian Forest Museum at the Highlands Nature Sanctuary, shows Hopewell Culture village life on a hillside overlooking the Seip Mound Ceremonial Center, located east of Bainbridge, Ohio.

Hopewell Culture: Of the many peoples inhabiting the Great Eastern Forest in what is now the United States, the Hopewell Culture, spanning 50 B.C. to 400 A.D., was one of most geographically influential. The Hopewell peoples were not the only American Indians to build earthworks, but they certainly were the most consummate. Their works ranged from solitary mounds and earthwork enclosures to immense sacred landscapes with multiple and connecting features, sometimes aligned to cosmic celestial events. The most complex of the Hopewell earthworks covered 1500 acres of land. In these complexes, earthen walls averaging 4-8 feet tall often enclosed collections of mounds, bordered walkways, and outlined vast geometric shapes. Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of the greatest ceremonial centers was the presence of one or more Greathouses. These timber pole halls were the locations of burials, cremations, and possibly other ceremonies. After they had served their intended purpose, Greathouses were burnt to the ground and mounded over with earth. Sometimes a new Greathouse was erected upon the ruins of the former, causing the mound to grow in size. Tremper Mound was an example of such a Greathouse.

Like Stonehenge and many other ancient monuments, some of the Hopewell Culture’s earthworks show remarkable astronomical alignments, marking solstice and lunar standstill points on the horizon. These alignments highlight the Hopewell people's sophisticated understanding of astronomy and their ability to integrate this knowledge into their architecture and ceremonial practices.

The indigenous history of the Eastern North American continent is the most under-rated and under-appreciated story in American history. American Indian history, when it is given attention, is often more focused on the indigenous tribes in the western half of the United States. In the East, most of our Native American earthworks were destroyed in the fifty years following European settlement, either by plow, excavation, or development. Of the many people inhabiting the Eastern Forest, the culture known as the Hopewell, living between 2,200 and 1,500 years ago, were one of the most artistic peoples to have ever lived on our continent.

Tremper Mound Culture History: Tremper Mound was constructed on the west terrace of the Scioto River late in the first century B.C. which was quite early in the Hopewell Cultural era. Tremper Mound’s irregularly shaped 8-foot tall mound was built on the ruins of a Greathouse and enclosed by an oval earthen wall that was 500 feet across - an unusually large span for a solitary mound. Early historians believed that Tremper Mound’s unusual shape was meant to portray an animal. However, an archaeological excavation that took place in 1915 revealed that the mound’s conformation mirrors the shape of the large timber hall buried beneath it. When the Greathouse was actively used by the Hopewell, it was divided into chambers, each alcove’s outer boundaries defined by vertical wooden poles. Walls were likely filled in with natural fibers to provide privacy and to create defined space. Whether or not the building was roofed is still unknown. Some of the chambers were dedicated to cremating the deceased, others had specially constructed basins that communally held the ashes of hundreds of community members. There was even a chamber that seemed to have primarily served as a kitchen, presumably to feed the attendees and workers.

The Greathouse included fire pits, possibly for ceremonial fires, and a large communal cache of over 500 articles, surmised to have been part of ancient ceremonies. Many if not most of these articles were broken - by the tests of time, the great fire that marked the end of the Greathouse, or by the original givers - we do not know. In the Hopwell tradition, the Greathouse was eventually burnt to the ground and then heaped over with layers of earth to form the Tremper Mound feature we know it today. Later in time, as many as 16 burials took place on Tremper Mound by digging graves into its surface. These were the only non-cremated burials ever found at Tremper Mound and they represent a later indigenous era.

Tremper Mound Excavation: In 1915 the largest disturbance ever inflicted on the mound came in the form of its full excavation by archaeologist, William C. Mills. A man representative of his time, he oversaw an exhumation of what was discovered to be the 2,000-year-old resting place of close to 400 cremated Native American Indians. Although Mill’s excavation uncovered an immense amount of historic information and art pieces, and although his records were meticulous and publicly shared, in the eyes of many living American Indians, the excavation was a disruption to an ancient sacred site, an act that will be difficult to atone.

Portsmouth Works: Tremper Mound was part of a large and majestic complex of earthworks that existed just 4-5 miles south of Tremper Mound near the confluence of the Scioto and the Ohio River. Known as the Portsmouth Works, the complex spanned both sides of the Ohio River in three main centers of development. Two separate ceremonial grounds stood on the river’s south bank on the Kentucky side, roughly six miles apart. A third complex stood on the north bank of the river on the Ohio side, showcasing, among other features, two large and striking horseshoe mounds.

Three walkways, each dramatically bordered with earthen walls, originated out of the Ohio side of the complex. Two walkways veered southward, each covering miles of uneven terrain to reach one of the two earthwork complexes that lay on the Kentucky side of the river. The only major obstacle between these ceremonial centers was the Ohio River, itself. How the Indians crossed the Ohio River, whether by swimming or canoeing, and whether such crossings were accomplished ceremoniously or pragmatically, remains a mystery. The third walled avenue left the Ohio complex in a westerly direction, leading to destinations unknown - possibly to Tremper Mound.

Today, nearly all of the Portsmouth Works on the Ohio side of the river lie buried beneath the city of Portsmouth. On the Kentucky side, most of the earthworks were similarly destroyed by development and farming.